Will higher education in the 21st century belong to China?

The time is right for Europe’s universities to make Chinese connections, say Ka Ho Mok and Jin Jiang in Times Higher Education.

Times Higher Education recently announced in its BRICS and Emerging Economics University Rankings 2017 that India has increased its share of top universities, but China still has the highest density of leading universities in the developing world.

In the BRICS rankings, Chinese universities occupy six of the top 10 positions. There is a growing trend for governments in the Asia and Pacific region to focus on gaining ‘world-class status’ for a few select universities, despite the fact that there is little agreement on how to define a world-class university.

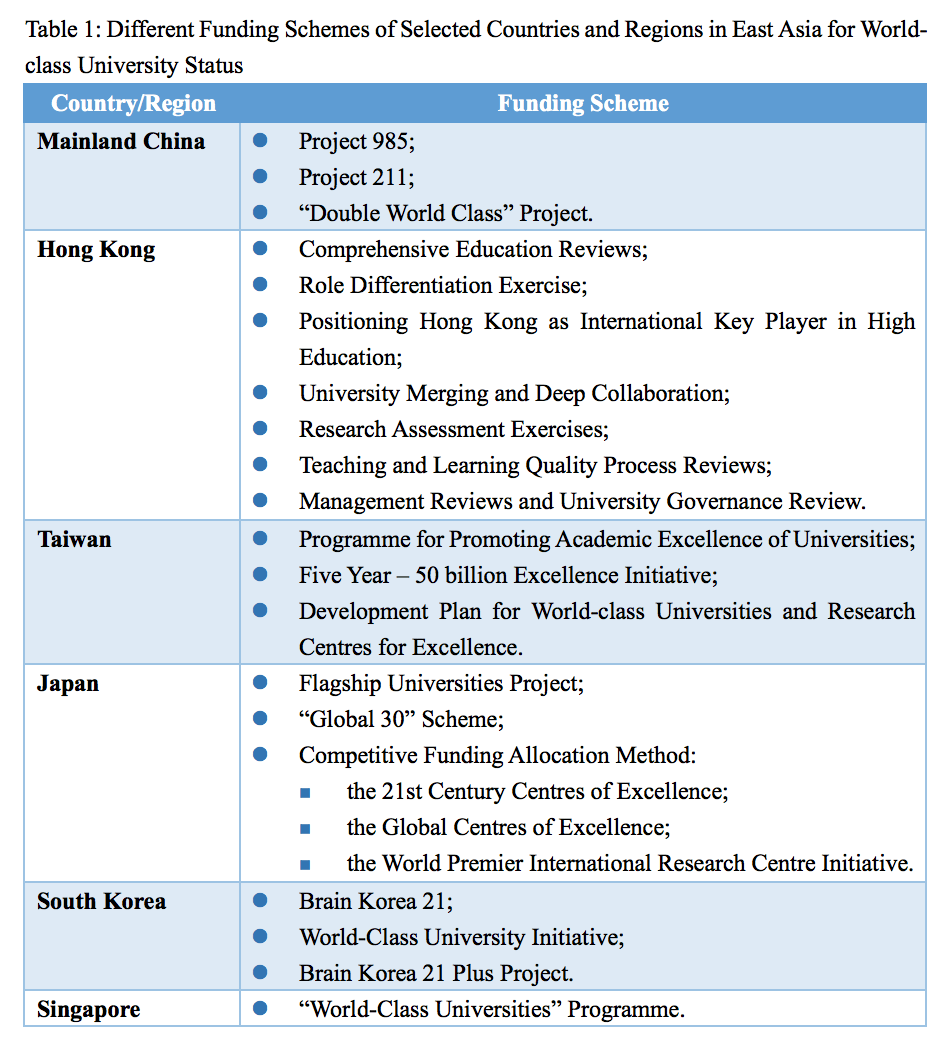

In this context, global rankings are perceived as a zero-sum competition. The table below presents some of the many different schemes adopted by Asian countries to enhance the competitiveness of their selected universities in international rankings. China, like other Asian countries, has made serious efforts to ensure world-class status for its universities.

Criteria compiled by Jamil Salmi, former coordinator of the World Bank’s tertiary education programme, measure world-class university status in terms of superior outputs, which include the production of qualified graduates who meet the requirements of the labour market, advanced research publishable by top scientific journals, and effective knowledge transfer in technical innovation and industry.

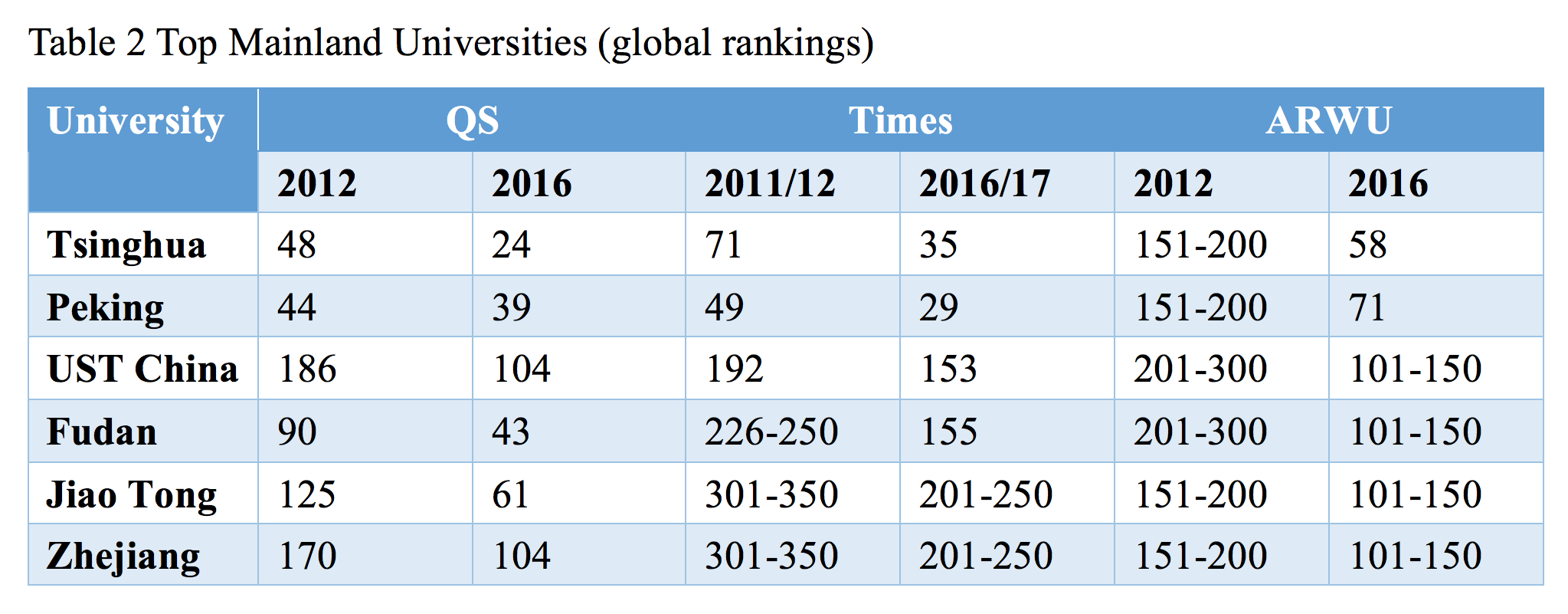

Using these criteria to measure the performance of China’s universities, the number ranked in the top 300 has increased from two to 13 over a period of 12 years. The table below shows how six selected public universities in China have steadily climbed the ladder in the Times Higher Education rankings and the Academic Ranking of World Universities, produced by Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

To tackle the problem of ‘brain drain’ in higher education, the Chinese state has been making great efforts to strengthen talent development. Attracting global talent to universities in mainland China is one of the country’s crucial strategic plans.

The Changjiang Scholars Programme, established in 1998, is an example of an initiative designed to attract global high-achieving academic scholars (for example, through providing professorships and achievement awards) to enhance the development of Chinese universities. The total investment in the programme in the first 10 years was approximately RMB454 million (approximately £52 million), of which RMB330 million – more than two thirds – came from China’s Ministry of Education.

Chinese dominance and implications for Europe’s universities

Given the rise of Chinese universities in global university rankings, will Chinese universities dominate higher education in the 21st century? The Chinese government has continued its investments in research and knowledge transfer related activities, reflecting the country’s political will to assert its regional and global leadership in higher education.

Most recently, the Chinese government rolled out the “Double World-class Project”, deliberately focusing funding support on selected academic and research fields of studies. This move will enhance the capacity of the selected areas, while the government has actively encouraged local universities to partner with leading universities overseas in promoting research and academic collaborations.

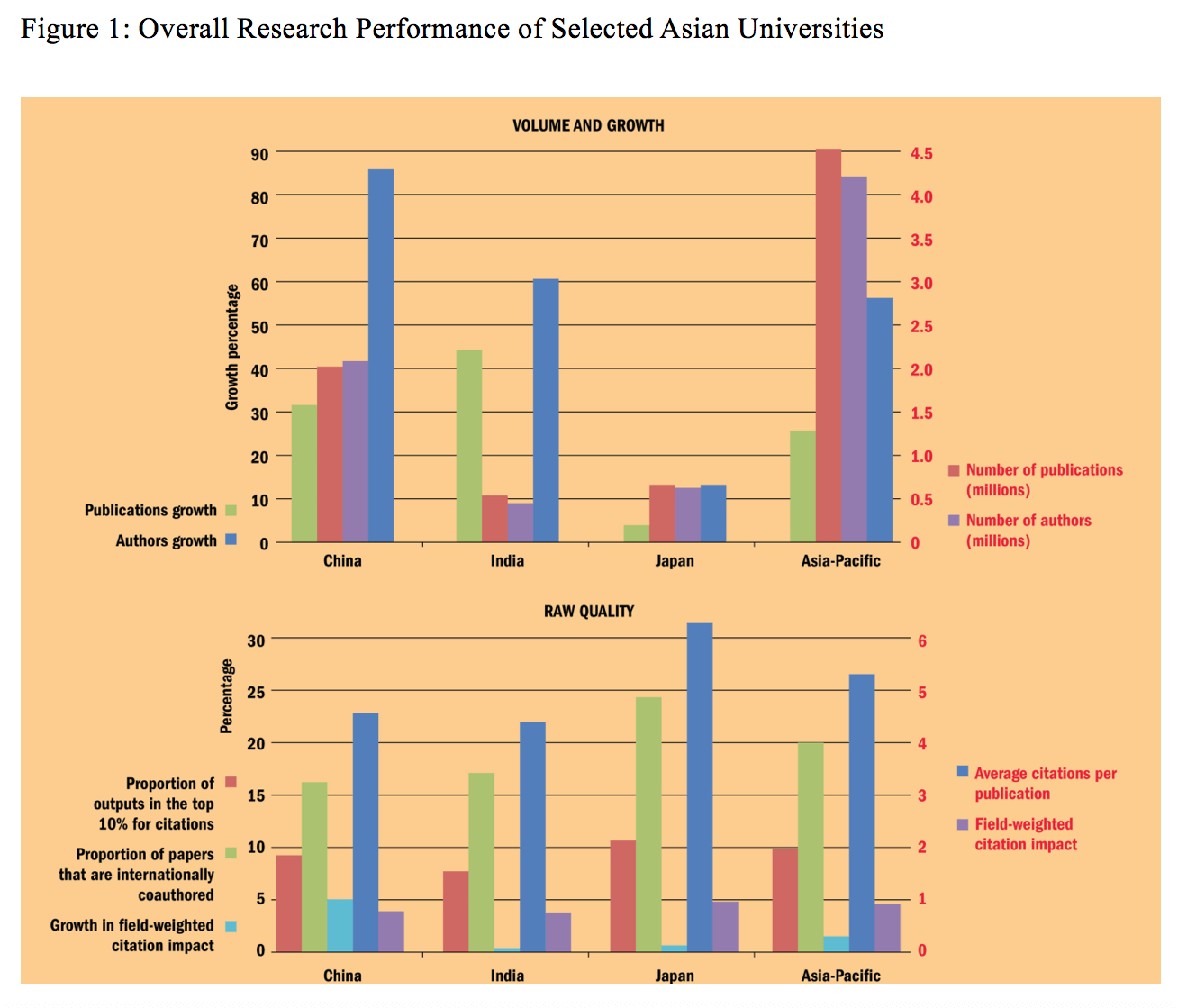

Given time, we would expect Chinese universities to scale new heights in producing internationally referred outputs and asserting world leadership in higher education. In this graph, based on Elsevier’s Scopus database, THE’s John Morgan shows the significant increase of research outputs produced by Chinese scholars, in terms of number of publications, citations and field-weighted citation impact.

What are the implications of the rise of these Asian universities for the UK and Europe, particularly after Brexit? UK universities should seriously consider branching out to the greater China region, and focus on capturing the opportunities on offer in terms of academic programme development and research collaborations.

European universities should also think seriously about their quality assurance systems and make appropriate changes to cater for the pressing demands of international and transnational higher education in Asia and greater China through forming partnerships in international studies programmes and research collaborations.

As the Chinese government is proactively promoting international collaboration, a number of funding schemes have been introduced to invite leading scholars / institutions overseas to foster collaboration. The rolling out of the ‘Double World-class Project’ will provide strategic investment from the Chinese government to promote inter-university collaboration, not only within the mainland but also internationally. It is vital that universities in Europe do not miss the opportunity to reach out to the Far East to facilitate deeper understanding of this part of the world.