Up, up and away: the era of high tuition fees

Dr Gill Wyness reports on research that would appear to support the current fee regime for ‘typical’ students on Wonkhe.

The UK’s relationship with tuition fees has always been an uneasy one. When the first fees were introduced in 1998, the response was student protests, sit-ins, walkouts, and the near ending of Tony Blair’s career.

Discontent of a similar nature accompanied the subsequent fee increases of 2006 and 2012. And now, nearly twenty years on, the question of who should pay for HE continues to be a highly emotive one, with Jeremy Corbyn promising to abolish fees in the 2017 Labour Party manifesto.

The bigger picture

But it’s not just in England that the ‘free college’ movement has been gaining momentum; in April of this year, New York became the first US state to offer free tuition to all but its wealthiest residents at its public four-year institutions. Meanwhile, Bernie Sanders continues to push for free public college tuition for all.

On both sides of the Atlantic, proponents of tuition fees argue that free university study is regressive since it means all taxpayers (including the poorest) get to foot the bill for students (who are disproportionality from advantaged backgrounds) to go to university and then reap higher rewards in the labour market. They also argue that charging for university can actually increase the proportion of disadvantaged students at university, by freeing up money to support poor students with financial aid and allowing the sector to expand. Those against fees meanwhile cite fears of rising debts, falling enrolment, and inequality.

Given that twenty years have passed since the introduction of fees in the UK, we now have the opportunity to look at the evidence. In a new Centre for Global Higher Education working paper with colleagues Richard Murphy and Judith Scott-Clayton, we study the UK’s transition from tuition fee-free university to some of the highest fees in the world, asking how these changes have impacted three major policy goals; university enrolments, equity, and university finances.

Enrol up

As other researchers have pointed out, it is an empirical challenge to estimate the impact of tuition fees (not to mention the other elements of HE finance) on participation. Instead of conducting a causal analysis, our study is purely descriptive. Our approach involves constructing appropriate measures of enrolments, access and quality, then tracking them over the time period before and after the introduction of tuition fees.

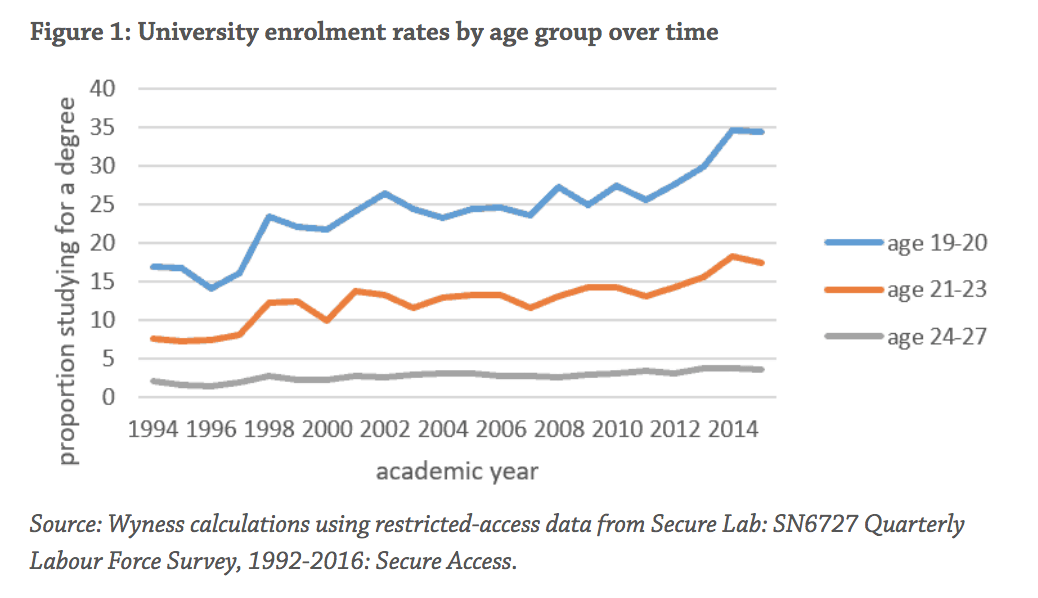

An initial examination of enrolment shows little evidence of a negative impact of fees. As Figure 1 below shows, enrolment rates among ‘typical’ students (aged 19/20 and studying full time), have more than doubled since the pre-fee era, rising from around 16 percent to around 35 percent in 2015. Participation among older age groups has also grown since the reforms.

All things being unequal

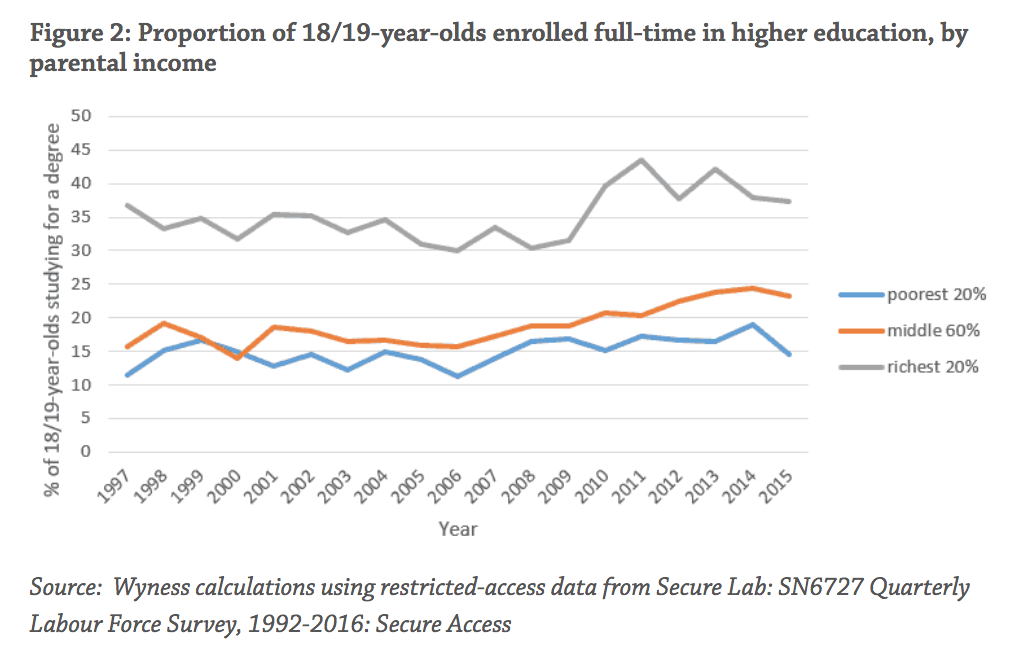

Perhaps of greater interest, however, is whether inequality in participation has worsened over the years since the reforms. There are reasons to be worried on this front. Work by Blanden and Machin, shows that those from rich families benefitted disproportionately from the HE expansion of the 1980s and 1990s. How has inequality fared since then? Figure 2 below, which uses Labour Force Survey (LFS) data on participation by parental income, shows that gaps between rich and poor, whilst still great, have not worsened since fees were introduced. This dataset has the advantage that we can link students to their parental incomes, but the resulting sample sizes are rather small.

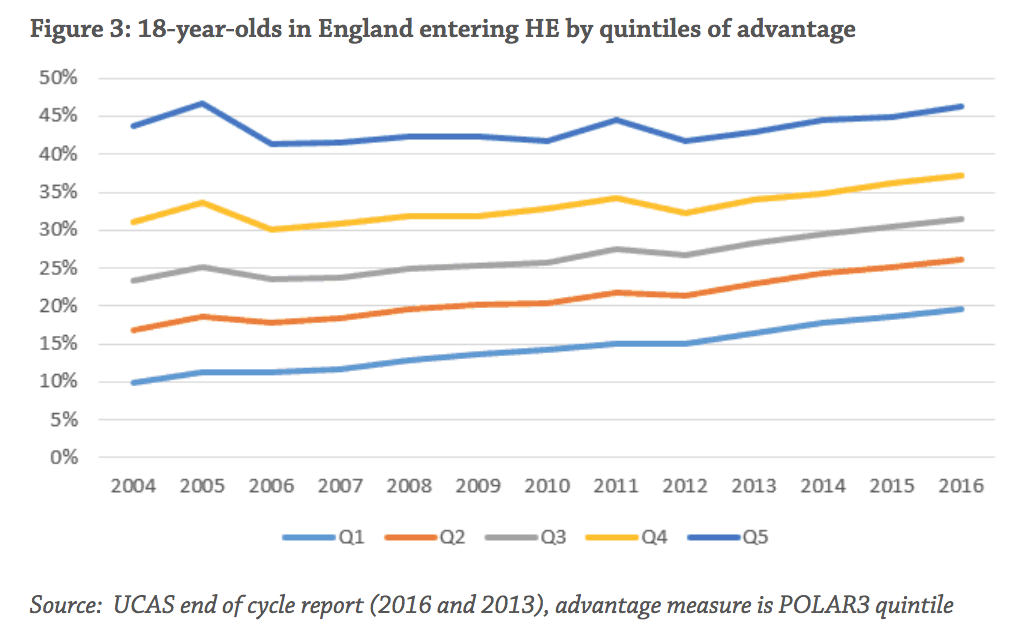

Figure 3 (below) presents an alternative measure of inequality, using UCAS data on the acceptance rates of ‘typical’ students from different backgrounds. Here we see that the proportion of students from the most disadvantaged quintile of households has approximately doubled, from 10% in 2004 (when the fees were capped at £1,000 per year, and free to most students) to 20% in 2016 (when all students paid £9,000 per year). Meanwhile, there has been little change in acceptances amongst the highest quintile of households.

Empirical studies have shown students to be responsive to prices, so how can it be that enrolments have gone up in the face of rising costs? The explanation may lie in the other changes to the HE finance system that accompanied fee increases. Since 2006 all fees have come with the offer of a government-backed income contingent loan, which allows students to borrow against their future incomes without fear of high repayment burdens of the type that students face in the US and other countries without income-contingent loan systems. Moreover, the last two decades have seen big increases in the amount of financial support available to students through loans and (until recently) grants. The poorest students can now access £8,500 per year in aid, compared to less than £5,000 per year (in real terms) in the period immediately before tuition fees. These elements of the system are crucial in protecting HE access.

Funding

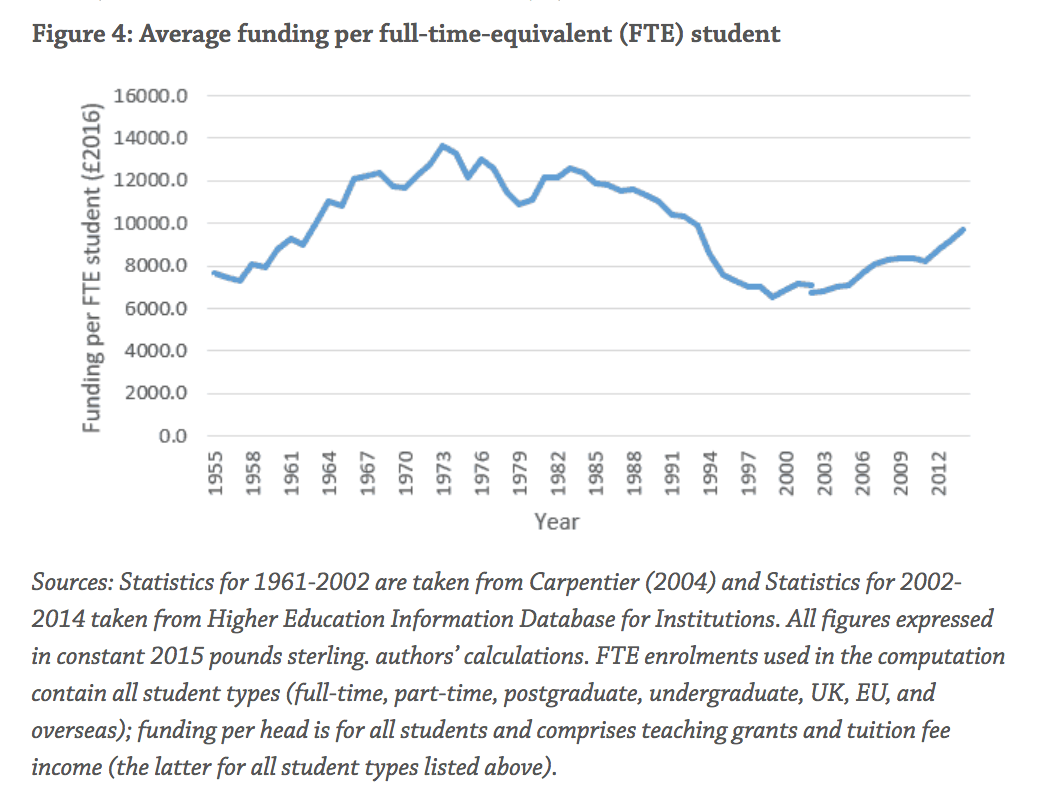

A final argument made by those in favour of fees concerns university finances. As Figure 4 below shows, under the fee-free era, university finances reached historical lows as the sector expanded and government investment failed to keep pace. University places were also capped (typical of free university systems – e.g. in Scotland), potentially squeezing out more marginal students who tend to be from disadvantaged groups. However, since 1999, funding per head has increased by nearly 50 percent and is now back at levels experienced in the early 1990s, with the caps on numbers completely removed. The chart highlights the key problem associated with free university systems, lack of investment.

The least-worst system

Of course, England’s system is not without its faults. The recent abolition of maintenance grants means that poor students now have the highest debts, which may threaten participation gains made amongst this group. Part-time student numbers have also suffered greatly as a result of the finance change, which seem to have affected them differently. Interest rates, at as much as 6.1% for the highest earning graduates, are relatively high and could potentially result in richer students exiting the loans system, which could threaten its stability. And finally, there is good evidence that many students do not fully understand the loans system, which could put off debt-averse students, who tend to be poorer.

But our evidence at least shows that the fortunes of universities have improved dramatically since the increase in private contributions through fees, and that any damage to enrolments and equity of typical students has been minimal.

This study was co-authored with Dr Richard Murphy (University of Texas at Austin) and Dr Judith Scott-Clayton (Teachers College, Columbia University).